Assembler Directives

Assembler directives are the instructions used by the assembler at the time of assembling a source program. More specifically, we can say, assembler directives are the commands or instructions that control the operation of the assembler.

Assembler directives are the instructions provided to the assembler, not the processor as the processor has nothing to do with these instructions. These instructions are also known as pseudo-instructions or pseudo-opcode.

Directives that Define SectionsThese directives associate portions of an assembly language program with the appropriate sections:

- The .bss directive reserves space in the .bss section for uninitialized variables.

- The .data directive identifies portions of code in the .data section. The .data section usually contains initialized data.

- The .intvec directive creates an interrupt vector entry that points to an interrupt routine name.

- The .retain directive can be used to indicate that the current or specified section must be included in the linked output. Thus even if no other sections included in the link reference the current or specified section, it is still included in the link.

- The .retainrefs directive can be used to force sections that refer to the specified section. This is useful in the case of interrupt vectors.

- The .sect directive defines an initialized named section and associates subsequent code or data with that section. A section defined with .sect can contain code or data.

- The .text directive identifies portions of code in the .text section. The .text section usually contains executable code.

- The .usect directive reserves space in an uninitialized named section. The .usect directive is similar to the .bss directive, but it allows you to reserve space separately from the .bss section.

Common Assembler

Directives:

1. Data Definition Directives in 8086 Assembly Language

Data Control Directives are special instructions in assembly language that guide the assembler on how to allocate, initialize, and organize data in memory. These directives are essential for defining variables, constants, arrays, and structures, enabling effective data management in 8086 microprocessor programs.

These directives do NOT generate machine code but control how the assembler interprets and places data in memory.

This directive is used for the purpose of allocating and initializing single or multiple data bytes.

DQ: Define Quad words

It is used to initialise quad words (8-bytes) either one or more than one. Thereby informing the assembler that the data stored in memory is quad-word.

DT: Define ten bytes

- Purpose: Allocates 10 bytes (80 bits) of memory.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- Supports extended-precision floating-point numbers.

DUP: Duplicate

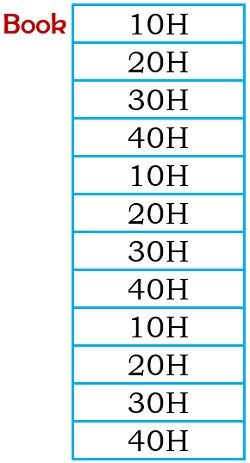

DUP allows initialization of multiple locations and assigning of values to them. This allows storing of repeated characters or variables in different locations.

![]()

So this permits the storing of these data in memory and creating 8 identical sets in the memory identified as Book.

DWORD: Double word

This directive is used to indicate that the operand is of double word size.

ALIGN

Syntax:

Explanation:

Improves performance, especially in systems with cache alignment requirements.

EVEN: It is used to inform the assembler to align the data beginning from an even address.

As data specified with an odd starting address requires 2 byte accessing. Thus using this directive, data can be aligned with an even starting address

OFFSET

Syntax:

Explanation:

Useful for pointer arithmetic and memory addressing.

Program Organization Directives

SEGMENT and ENDS

It is used to show the beginning of a memory segment with a specific name.

Syntax:

CODE_SEG SEGMENT ; code instructions CODE_SEG ENDS

SEGMENTstarts a new segment.ENDSmarks the end of that segment.

Advantages of Data Control Directives:

- 📌 Efficient Memory Management: Allocate precise memory as needed.

- 🚀 Performance Optimization: Use directives like

ALIGNfor faster data access. - ♻️ Reusability: Define constants with

EQUto simplify code maintenance. - 📊 Data Initialization: Pre-define data for immediate use during execution.

⚠️ Things to Watch Out For:

- ❌ Uninitialized Variables (

?): Can cause unpredictable behavior if accessed before initialization. - ❌ Memory Misalignment: Ignoring alignment can slow down data access, especially in modern processors.

ASSUMEPurpose: Tells the assembler which segment register points to which segment.

Syntax:

Explanation: Here,

CS (Code Segment) is linked to CODE_SEG, and DS (Data Segment) to DATA_SEG.This helps the assembler generate correct machine code for segment addressing.

ORG (Origin Directive)

Syntax:

ORG 1000h

- Explanation:

- Tells the assembler to begin assembling code/data at address

1000h. - Useful in embedded systems and memory-mapped programming.

- Tells the assembler to begin assembling code/data at address

END- Purpose: Marks the end of the source code file.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- Signals the assembler that no more code follows.

- Without

END, the assembler may generate errors.

PROCandENDP(Procedure Definition Directives)- Purpose: Define the start and end of a procedure (function).

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- Helps organize code into reusable procedures.

- Improves readability and modularity.

PUBLICandEXTERN- Purpose: Manage variable or procedure visibility across multiple files.

PUBLIC: Declares symbols (variables/procedures) accessible from other files.EXTERN: References symbols defined in other modules.- Example:

🚀 Sample Assembly Program Using Organization Directives

PTR: Pointer

This directive shows information regarding the size of the operand.

![]()

This shows legal near jump to BX.

PUBLIC: This directive is used to provide a declaration to variables that are common for different program modules.

STACK: This directive shows the presence of a stack segment.

SHORT: This is used in reference to jump instruction in order to assign a displacement of one byte.

THIS: It is used along with EQU directive for setting the label to either, byte, word or double-word.

3.

Equate Directive:

o EQU: Assigns a constant value to a symbol.

It is used to assign any numerical value or constant to the variable.

Example: PI EQU 3.14 (PI is now a constant)5 End Directive:

END: Marks the end of the source code for the assembler.

Example: END (Assembler stops reading beyond this point)

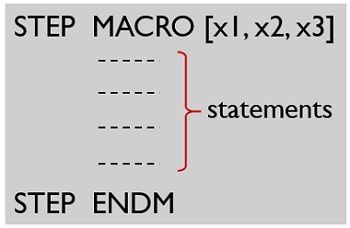

Shows the beginning of macro along with defining name and parameters.

ENDM: End of macro

ENDM indicates the termination of macro.

where macroname (STEP) is specified by the user.

Extern:

It is used to tell the assembler that the name or label following the directive are I some other assembly module. For example: if you call a procedure which is in program module assembled at a different time from that which contains the CALL instructions ,you must tell the assembler that the procedure is external the assembler will put information in the object code file so that the linker can connect the two module together.

Example:

PROCEDURE -HERE SEGMENT

EXTERN SMART-DIVIDE: FAR ; found in the segment; PROCEDURES-HERE

PROCEDURES-HERE ENDS

GLOBAL:

The GLOBAL directive can be used in place of PUBLIC directive .for a name defined in the current assembly module; the GLOBAL directive is used to make the symbol available to the other modules. Example:

GLOBAL DIVISOR:

WORD tells the assembler that DIVISOR is a variable of type of word which is in another assembly module or EXTERN.

SEGMENT:

It is used to indicate the start of a logical segment. It is the name given to the the segment. Example: the code segment is used to indicate to the assembler the start of logical segment.

It is used to identify the start of a procedure. It follows a name we give the procedure.

After the procedure the term NEAR and FAR is used to specify the procedure Example: SMART-DIVIDE PROC FAR identifies the start of procedure named SMART-DIVIDE and tells the assembler that the procedure is far.

It is used to give a specific name to each assembly module when program consists of several modules.

Example: PC-BOARD used to name an assembly module which contains the instructions for controlling a printed circuit board.

It is used to tell the assembler to insert a block of source code from the named file into the current source module. This shortens the source module. An alternative is use of editor block command to cop the file into the current source module.

It is an operator which tells the assembler to determine the offset or displacement of a named data item from the start of the segment which contains it. It is used to load the offset of a variable into a register so that variable can be accessed with one of the addressed modes. Example: when the assembler read MOV BX.OFFSET PRICES, it will determine the offset of the prices.

Value-Returning Attribute Directives in Assembly Language

Value-Returning Attribute Directives are special assembler directives that return information about variables, constants, or labels during the assembly process. They don’t generate machine code directly but provide metadata or attributes that the assembler can use to manage memory, data types, and program structure efficiently.

These directives are especially useful when dealing with macros, conditional assembly, or complex data structures.

LENGTH/LENGTHOF- Purpose: Returns the number of elements in an array.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- Here,

COUNTwill hold the value5because there are five elements inARRAY.

- Here,

SIZE/SIZEOF- Purpose: Returns the total size (in bytes) of a variable or data structure.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- Since each

DW(Define Word) is 2 bytes,SIZE_DATAwill be6(3 × 2 bytes).

- Since each

TYPE- Purpose: Returns the size of a single element in an array or the data type size of a variable.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

TYPE ARRwill return1because eachDB(Define Byte) is 1 byte.

OFFSET- Purpose: Returns the memory address offset of a variable or label relative to its segment.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- This instruction moves the offset address of

VARinto theSIregister.

- This instruction moves the offset address of

HIGHandLOW- Purpose: Extract the high or low byte of a word or address.

- Syntax:

Key Differences Between

Value-Returning Directives:

|

Directive |

Purpose |

Returns |

Example |

|

LENGTHOF |

Number of elements in an array |

Integer count |

LENGTHOF ARRAY → 5 |

|

SIZEOF |

Total size in bytes |

Byte size |

SIZEOF ARRAY → 5 |

|

TYPE |

Size of one data element |

Bytes per element |

TYPE ARRAY → 1 |

|

OFFSET |

Offset address in memory |

Address offset |

OFFSET VAR |

|

HIGH / LOW |

High/Low byte of a word/address |

High byte or Low byte of a value |

HIGH 1234h → 12h |

Procedure Definition Directives in 8086 Microprocessor

In 8086 assembly language programming, procedures are blocks of code designed to perform specific tasks, much like functions in high-level languages. They help organize code into reusable, manageable sections.

To define and manage these procedures, we use Procedure Definition Directives, primarily PROC and ENDP. These directives help the assembler recognize where a procedure starts and ends.

PROC(Procedure Directive)- Purpose: Marks the beginning of a procedure.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

NEAR: Indicates the procedure is in the same code segment (default in small memory models).FAR: Indicates the procedure is in a different segment (used in large memory models).

ENDP(End Procedure Directive)- Purpose: Marks the end of a procedure.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- Must match the name used with

PROCto ensure proper procedure closure.

- Must match the name used with

CALL(Procedure Call Instruction)- Purpose: Transfers control to the procedure.

- Syntax:

RET(Return Instruction)- Purpose: Returns control to the calling program after procedure execution.

- Syntax:

🚀 Types of Procedures in 8086

Near Procedures:

- Stay within the same code segment.

- Use

CALLandRETwithout modifying theCSregister. - More efficient due to fewer clock cycles.

Far Procedures:

- Located in a different segment.

CALLpushes bothIP(Instruction Pointer) andCS(Code Segment) onto the stack.- Requires a

FAR RETto pop both values.

Macro Definition Directives in 8086 Assembly Language

In 8086 assembly language programming, macros are powerful tools that allow you to define reusable code blocks. They are similar to functions or procedures in high-level languages but differ in how they are processed. Macros are handled by the assembler during compilation, meaning they are expanded inline wherever called, leading to faster execution at the cost of increased code size.

MACRODirective- Purpose: Defines the beginning of a macro.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

MACRO_NAMEis the name used to call the macro.- Optional parameters can be passed for dynamic operations.

ENDM(End Macro Directive)- Purpose: Marks the end of a macro definition.

- Syntax:

Macro Invocation (Calling a Macro)

- Purpose: Calls the macro, expanding its code inline.

- Syntax:

- Advantages of Using Macros:

- ✅ Faster Execution: No runtime overhead like procedure calls (no

CALLorRETinstructions). - ✅ Code Reusability: Write once, use multiple times.

- ✅ Simplified Code: Reduces redundancy and improves readability.

- Disadvantages of Macros:

- ❌ Increased Code Size: Since macros are expanded inline, large macros can cause code bloat.

❌ Limited Debugging: Harder to debug because there’s no separate stack frame like in procedures.

Macros vs Procedures:

|

Aspect |

Macros |

Procedures |

|

Definition |

Defined using MACRO and ENDM |

Defined using PROC and ENDP |

|

Execution |

Expanded inline at compile time |

Called at runtime using CALL |

|

Speed |

Faster (no call/return overhead) |

Slower due to call/return

instructions |

|

Memory Usage |

More (due to code duplication) |

Less (code stored once) |

|

Debugging |

Harder |

Easier (stack trace available) |

Branch Displacement Directives in 8086 Assembly Language

In assembly language programming, branch displacement directives are used to control the range of jumps (branches) within a program. These directives guide the assembler on how far a branch instruction (like JMP, CALL, JE, etc.) can jump relative to the current instruction. This is crucial for optimizing both memory usage and execution speed.

What is Branch Displacement?

When using jump instructions, the CPU needs to know where to jump. This is done using a displacement, which is the difference between the current instruction’s address and the target address. The displacement can be:

- Short (8-bit displacement) – For jumps within -128 to +127 bytes from the current instruction.

- Near (16-bit displacement) – For jumps within the current code segment (range: ±32,768 bytes).

- Far (Inter-segment jump) – For jumps to a different code segment, requiring both segment and offset addresses.

📋 Branch Displacement Directives in 8086

The assembler provides branch displacement directives to explicitly control how it handles these jumps:

SHORTDirective- Purpose: Forces the assembler to generate an 8-bit displacement jump.

- Syntax:

- Range: -128 to +127 bytes from the current instruction.

- ✅ Benefits: Faster and smaller in size (2 bytes total).

NEARDirective- Purpose: Instructs the assembler to perform a 16-bit displacement jump within the same code segment.

- Syntax:

- Range: ±32,768 bytes.

- ⚡ Benefits: Used for larger jumps within the same segment.

FARDirective- Purpose: Indicates a far jump (inter-segment), requiring both the segment and offset addresses.

- Syntax:

- Range: Anywhere in memory (across segments).

- 🌍 Benefits: Enables jumps beyond the current segment, commonly used in large applications or OS-level code.

OFFSETDirective (Related)- Purpose: Retrieves the offset address of a label for use in jump instructions.

- Syntax:

🗒️ Advantages of Using Branch Displacement Directives

- 🚀 Optimized Performance: Short jumps are faster and more memory-efficient.

- 🧩 Flexible Control Flow: Near and far jumps allow complex program structures.

- 🎯 Precise Memory Management: Explicitly control jump ranges to optimize large programs.

⚠️ Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Out-of-Range Errors:

- Trying to use

SHORT for a jump beyond ±127 bytes will cause an assembler error. - Fix: Switch to

NEAR or remove the SHORT directive for auto-detection.

Segment Boundary Issues:

NEAR jumps fail if the target is in a different code segment.- Fix: Use

FAR jumps for inter-segment transitions.

Unaligned Jumps:

- Inefficient jump placements can lead to performance hits, especially in loops.

- Fix: Use the

ALIGN directive to align critical code for faster access.

Out-of-Range Errors:

- Trying to use

SHORTfor a jump beyond ±127 bytes will cause an assembler error. - Fix: Switch to

NEARor remove theSHORTdirective for auto-detection.

Segment Boundary Issues:

NEARjumps fail if the target is in a different code segment.- Fix: Use

FARjumps for inter-segment transitions.

Unaligned Jumps:

- Inefficient jump placements can lead to performance hits, especially in loops.

- Fix: Use the

ALIGNdirective to align critical code for faster access.

🎯 Real-World Scenario: Loop Optimization

- Why

SHORT? Loops are tight, so SHORT keeps the code fast and compact.

SHORT? Loops are tight, so SHORT keeps the code fast and compact.🔑 Key Takeaways:

- Use

SHORT for tight loops and conditions (fast & small). - Use

NEAR for moderate jumps within the same segment. - Use

FAR for inter-segment program flow in large applications. - Always be mindful of the jump distance to avoid assembler errors.

SHORT for tight loops and conditions (fast & small).NEAR for moderate jumps within the same segment.FAR for inter-segment program flow in large applications.Operators perform operations like arithmetic, logical comparisons, and data manipulation.

1.

Arithmetic Operators:

o +

(Addition), - (Subtraction), * (Multiplication), / (Division)

o Example: MOV

AX, 5 + 3 (AX = 8)

2.

Logical Operators:

o AND,

OR, NOT, XOR

o Example:

MOV AL, 0Fh

AND AL, 03h ; AL = 03h after operation

3.

Relational Operators:

o ==,

!=, <, >, <=, >= (Used in conditional assembly)

o Example:

IF AX == BX

MOV CX, 0

ENDIF

4.

Shift and Rotate Operators:

o SHL

(Shift Left), SHR (Shift Right), ROL (Rotate Left), ROR (Rotate Right)

o Example: SHL

AL, 1 (Shift AL left by 1 bit)

5.

Bitwise Operators:

o &

(AND), | (OR), ^ (XOR), ~ (NOT)

✅ Key Differences Between Directives

and Operators:

|

Aspect |

Assembler Directives |

Operators |

|

Purpose |

Guide the assembler |

Perform computations or logic |

|

Execution |

Not executed by the CPU |

Executed during program runtime |

|

Examples |

DB, DW, EQU, ORG, END |

+, -, AND, OR, SHL |

|

Impact |

Affects memory layout, code

structure |

Affects data manipulation |

· File Inclusion Directives in 8086 Assembly Language

File Inclusion Directives in assembly language allow you to include external files into your source code during the assembly process. This helps in organizing large projects by separating code into modular, reusable parts, such as header files, macros, procedures, or constant definitions.

These directives are handled by the assembler and do NOT generate machine code. Instead, they control how the assembler processes and integrates the included files into the final program.

🚀 Why Use File Inclusion Directives?

- ✅ Modularity: Break large codebases into manageable modules.

- ✅ Reusability: Reuse common code (macros, constants) across multiple programs.

- ✅ Maintainability: Update shared code in one place, and it reflects everywhere.

- ✅ Readability: Keep the main code clean and focused.

📋 Common File Inclusion Directives

INCLUDEDirective- Purpose: Inserts the contents of an external file directly into the source code at the specified point.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- The assembler copies everything from

filename.asminto the current file during assembly. - Often used for including macro libraries, constants, or procedures.

- The assembler copies everything from

INCLUDELIBDirective (MASM-specific)- Purpose: Links an external library file during the assembly process.

- Syntax:

- Explanation:

- Instructs the assembler to link with a specified

.libfile. - Used in advanced assembly programming, often with external modules or drivers.

- Instructs the assembler to link with a specified

Benefits of Using File Inclusion

Directives

|

Advantage |

Explanation |

|

✅

Modularity |

Keeps code organized by separating

into modules. |

|

✅

Reusability |

Share macros, constants, and

procedures across files. |

|

✅

Maintainability |

Update code in one place; changes

reflect globally. |

|

✅

Simplified Code |

Reduces clutter in the main

program. |

⚠️ Common Issues & How to Avoid Them

File Not Found Error:

- Problem: The assembler can't find the included file.

- Fix: Ensure the file path is correct or use relative paths.

Multiple Inclusion Conflicts:

- Problem: Including the same file multiple times can cause redefinition errors.

- Fix: Use include guards (conditional assembly directives).

Incompatible Libraries:

- Problem: Linking incompatible

.libfiles may cause linker errors. - Fix: Ensure library compatibility with the assembler version.

🎯 Target Machine Code Generation Control Directives in 8086 Assembly Language

Target Machine Code Generation Control Directives are special instructions provided to the assembler to control how the machine code (binary code) is generated from assembly language. These directives do NOT generate machine code themselves but guide the assembler in structuring, optimizing, or managing the final executable.

These directives are crucial for memory management, code optimization, segment handling, and linking with other modules in complex applications.

🚀 Why Are They Important?

- ✅ Optimize Code Size and Performance: Fine-tune the generated machine code for speed or space efficiency.

- ✅ Control Memory Layout: Place code/data in specific memory segments.

- ✅ Facilitate Linking: Manage external references and module-level code organization.

- ✅ Ensure Compatibility: Align with specific hardware or system requirements.

📋 Common Target Machine Code Generation Control Directives

SEGMENT&ENDSDirectives- Purpose: Define code, data, or stack segments in memory.

- Syntax:

ASSUMEDirective- Purpose: Informs the assembler about the default segment registers to use.

- Syntax:

ORGDirective- Purpose: Sets the starting address for code or data in memory.

- Syntax:

- Use Case: Align data/code at specific memory locations.

ALIGNDirective- Purpose: Aligns code or data on specific memory boundaries (e.g., 2, 4, 16 bytes).

- Syntax:

- Benefit: Improves performance, especially in loops or hardware-specific code.

EVENDirective- Purpose: Ensures the next instruction starts at an even memory address.

- Syntax:

- Why Important? 8086 can access even-aligned data faster.

PUBLIC&EXTERNDirectives- Purpose: Control external linking between different modules.

- Syntax:

GROUPDirective- Purpose: Combines multiple segments into a single logical group.

- Syntax:

PROC&ENDPDirectives- Purpose: Define procedures (functions) in assembly.

- Syntax:

ENDDirective- Purpose: Marks the end of the source file and specifies the program’s entry point.

- Syntax:

✅ Benefits of Using These Directives

- 🚀 Performance Optimization: Directives like

ALIGNandEVENimprove execution speed. - 🧩 Modular Code Organization:

PUBLICandEXTERNsupport multi-file projects. - 📊 Efficient Memory Layout:

ORGandGROUPhelp control data/code placement. - 🔄 Reusable Procedures:

PROCandENDPallow structured programming.

⚠️ Common Errors & How to Avoid Them

Misaligned Data:

- Problem: Not aligning data can cause performance degradation.

- Fix: Use

ALIGNandEVENdirectives.

Segment Register Mismatches:

- Problem: Incorrect

ASSUMEsettings lead to runtime errors. - Fix: Always align

ASSUMEwith actual segment usage.

- Problem: Incorrect

External Linking Issues:

- Problem: Missing

PUBLIC/EXTERNdeclarations cause linker errors. - Fix: Verify all external symbols are correctly declared.

- Problem: Missing

Incorrect Memory Addressing:

- Problem: Using

ORGwithout understanding memory layout can cause overlaps. - Fix: Carefully plan memory map when using

ORG.

🔍 Key

Differences Between Assembler Directives and Instructions

|

Aspect |

Assembler Directives |

Instructions (Machine

Instructions) |

|

Purpose |

Guide the assembler on code

organization, data definition, etc. |

Instruct the CPU to perform

specific operations. |

|

Executed By |

Assembler (during

assembly time) |

CPU (during program

execution) |

|

Generates Machine Code? |

❌

No |

✅

Yes |

|

Effect on Program |

Affects how code is assembled but

doesn’t affect runtime behavior directly. |

Directly affects the program’s

execution. |

|

Examples |

DB, DW, EQU, SEGMENT, ORG, ASSUME |

MOV, ADD, SUB, JMP, INT, INC |

|

When It Works |

During the assembly process |

During runtime (program

execution) |

|

Memory Allocation |

Can allocate memory (e.g., using DB,

DW). |

Uses allocated memory but does not

allocate it. |

|

Control Type |

Controls code generation and

layout. |

Controls CPU operations and program

flow. |

|

Error Handling |

Errors detected during assembly

time. |

Errors (like invalid operations)

occur at runtime. |

No comments:

Post a Comment